You may have noticed that the fruit bags in your supermarket have for a while now been labelled as biodegradable. These shall not be confused with the bags you are given (or rather charged for) at the cashier, which are recycled.

A biodegradable material in the presence of oxygen is converted into CO2 and water by the action of microorganisms in the natural environment, whether terrestrial or aquatic. Unlike most conventional plastics, whose molecular chains are composed exclusively of carbon atoms, biodegradable plastics have oxygen atoms resulting from ester bonds in their molecular structure. These make these chains weaker against the action of certain bacteria and fungi capable of breaking them in periods ranging from a few weeks to a few years, depending on environmental conditions. This is not comparable to conventional plastics, which in low-energy environments, at least in theory, have the potential to persist for centuries. If in addition, we take into consideration that we can make biodegradable plastics from biomass instead of fossil fuels, we can turn these materials into renewable resources.

But not all are advantages. On the one hand, it is technically more difficult to make biodegradable plastics, so they are more expensive and may require more chemical additives to achieve the same mechanical properties as lifelong polyethene. On the other hand, when they decompose, they can release chemicals or nanoparticles with harmful effects on organisms. In this second issue, we are working funded by the "Agencia Española de Investigación" (AEI) in the framework of the RisBioPlas Project, coordinated by the UDC.

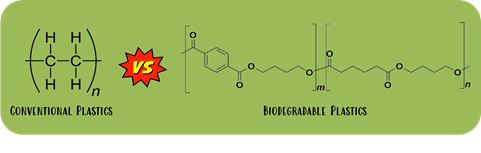

To evaluate the potential effect of plastics on organisms, we prepare extracts from plastic powder mixed with seawater, which we call leachate. The idea is that any chemical carried by the plastic goes into the water and we can identify its presence through chemical analysis or biological testing. If we incubate sensitive marine organisms, such as sea urchin larvae, in these leachates, the larvae will detect the presence of any harmful chemicals, even at very low concentrations, and will present in that case an abnormal development. In the photo on the left you can see a sea urchin larva incubated in marine leachate from a polyethene bag prepared by mixing 1 g of plastic per litre of water and diluting to 1/3, and on the right three larvae incubated in leachate from a prepared biodegradable bag in the same way. As it can be seen, the latter have smaller sizes and various morphological aberrations.

We are currently trying to identify these toxic effects from chemicals present in the biodegradable bags or derived from their degradation so that before deciding on replacing the harmless polyethene with other materials, no matter how "bio" they are, we are sure that the remedy is not worse than the disease.

© 1995 - 2026 Equipo de investigación ECOTOX.